Deep-Diving Robots Zap, Kill Invasive Lionfish

The robotics company iRobot, known for creating the autonomous and endearing Roomba vacuums, is taking steps to make a clean sweep of lionfish in the coastal waters of the Atlantic Ocean, with a robot designed to target and dispatch the invasive fish.

A diving robot will enable individuals on the ocean surface to remotely zap and kill lionfish with electrical charges. The effort is meant to help curb the fast-growing populations of these voracious predators, which are recognized by environmental officials as a serious threat to marine ecosystems in the western Atlantic.

The initiative to launch the lionfish-targeting robot is called Robots in Service of the Environment (RISE) and represents an iRobot partnership with organizations and volunteer experts in the fields of robotics, engineering and conservation. The lionfish project is the first RISE effort to address environmental challenges with robotic solutions, according to a statement on the RISE website. [The 6 Strangest Robots Ever Created]

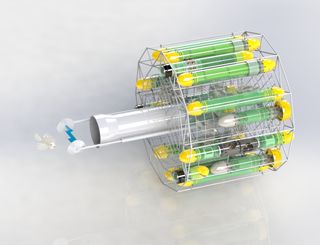

3D renders of the robot show a remotely controlled device equipped with a camera, so that users can track the lionfish remotely. At the front of the robot are two discs mounted on rods and facing each other. When the fish is positioned between the discs, the robot's operator triggers a lethal electrical shock; the robot then collects the fish in a net or cage to bring it up to the surface.

The first generation of robots will measure about 2.5 feet (0.8 meters) in length, according to John Rizzi, executive director of RISE. The team's goal is to design compact robots suitable for recreational hunters, as well as larger models to accommodate greater numbers of lionfish for commercial hunters, Rizzi told Live Science. Production and in-water testing of working prototypes is anticipated for November, Rizzi said.

Deadly invaders

Lionfish is the common name for the Pterois genus, which contains 12 species. They are striking to look at, as their bodies are covered in bold stripes and delicate, fluttering fins that are offset by rows of venomous spines, making them a popular choice for aquarium owners. Native to Indo-Pacific ocean waters, the flashy-looking predators can measure between 2 and 17.7 inches (5 and 45 centimeters) long, weighing up to 2.9 pounds (1.3 kilograms).

If only the non-native lionfish had stayed confined to their aquariums. But for more than two decades, invasive lionfish have been breeding in the Atlantic Ocean and in the Caribbean Sea at an alarming rate. And with no natural predators in those regions to keep their numbers in check, lionfish are decimating native fish populations.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In Florida and in the Bahamas, where native fish and coral reef ecosystems have been especially hard-hit by booming lionfish numbers, environmental officials have organized hunting events encouraging divers to catch as many lionfish as possible. Research showed that the hunts can help native fish rebound, but they are most effective when targeting small areas, and won't control lionfish populations on a larger scale.

Could diving robots help conservationists gain control of these invasive pests? Rizzi told Live Science that they could, by allowing users to target deeper waters where lionfish breed, and where diving hunters typically can't go.

"The average recreational diver stays close to shore and can only dive to 80 to 100 feet [24 to 30 meters]," Rizzi explained. "Big colonies of lionfish have been found down to 900 feet [274 m]. We believe this device is the only way to economically kill populations off at greater depths."

Diving robots would need to get very close to their targets to deliver the killing shock, and tests showed that the lionfish didn't seem spooked by an approaching robotic hunter, Rizzi said. While other fish would quickly swim away when approached with probes similar to those the robot would carry, lionfish didn't respond — perhaps because they aren't used to being hunted by natural predators in that region, Rizzi suggested.

"We'll be their first predator," he said. "They won't see us coming."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.